The TDC’s Annual Competition is in its 69th year and we’re thrilled to have a global panel to jury this year’s entries of typographic design excellence. Our jury consists of some of the brightest minds in typography, as design practitioners and as thought leaders in design advocacy. We reached out to Diana Haj-Ahmad, who is on the Typography discipline panel to share her experience in her journey from growing up in Palestine to training as a designer in Boston, NYC, and SF, her observations and reflections on typography and design in the Middle East, her trajectory towards being a design advocate at IDEO.org, also on what she’s looking forward to see in the upcoming typography submissions.

You were born in Jordan, grew up in Palestine, and trained in design in Boston, NYC, and SF; How has your unique background shaped your creative process and passion for design advocacy?

I was born in a household of 7, and I was the youngest child. I was either always surrounded by others or left to my own devices and imagination. Laying on the ground, I would dream up entire worlds by examining the details of objects surrounding me: their form, color, texture, sound, or smell. Growing up in Palestine opened my eyes to the possibilities, in a world that lacks most freedoms you run away into your own imagination by designing an alternate world that has less limitations, more possibilities, and similar beauty. Later, I was fortunate enough to be able to leave and study in Boston. I remember thinking “what have I gotten myself into?“, but soon enough Boston introduced me to art history and design through surrounding institutions and academia. I was in my sponge phase; in a new and foreign place I was taking everything in and learning. Once that sponge was saturated I started reflecting on Boston’s limitations — the lack of diversity and openness to veer off a traditional professional path. I was craving experimentation and variety, and so I left to NYC to pursue an MFA in Design Entrepreneurship at the School of Visual Arts. In New York I fell in love with the chaos. It fed my soul with ideas and opened my eyes to opinions, expressions, and cultures that I haven’t experienced. I also met many people that fueled me with energy and ambition and encouraged me to go after my own ideas. In my final pitstop in San Francisco, I joined IDEO.org and learned what it means to stand for what I believe in, to express my values and beliefs through design, to be in community with others that are working towards a similar purpose and mission. And I’m grateful for that!

In the West, the perception of the Middle East tends to zero in on [war and diaspora]. What would you like people to know about typography and design from the Middle East?

First, I must say that I didn’t get to professionally practice in the Middle East. While I’m disconnected in the practical sense, I do observe and reflect. What’s important to note here is that the West didn’t only zero in on the negatives of the Middle East, but in doing so it alienated the East and left its richness out of the fundamentals of design. The curriculums, influencers, and references center Western art and design movements, champion Swiss grids, and highlight typefaces designed with Latin characters in mind first. And the problem is that the East is also using these same references and examples in teaching and training the next generation of designers. While I completely respect and admire what was produced, I do think that the Middle East has a vivid history, language, and artistry to look at and incorporate. Whether it’s hand painted signs in the markets, embroidery on traditional dresses, or the making and embossing process of olive oil soaps, and the list goes on. These crafts and artisans should be a compass and reference to typography and design as well. Not only in their aesthetic, but in their stories and purpose that they fulfill. There’s nothing that brings me more joy than seeing Felfel, for example, a typeface designed by Boharat and inspired by Egyptian hand painted street signs. So I do recognize that there’s already progress towards better understanding and referencing these skills and crafts, and I hope that it continues to be done ethically with the mindset and goal to decolonize design and redefine what “good” looks like.

Tell us a little bit about your experience as a designer at IDEO.org – How do projects get conceived? How has your work developed over time? What significant discoveries have you made?

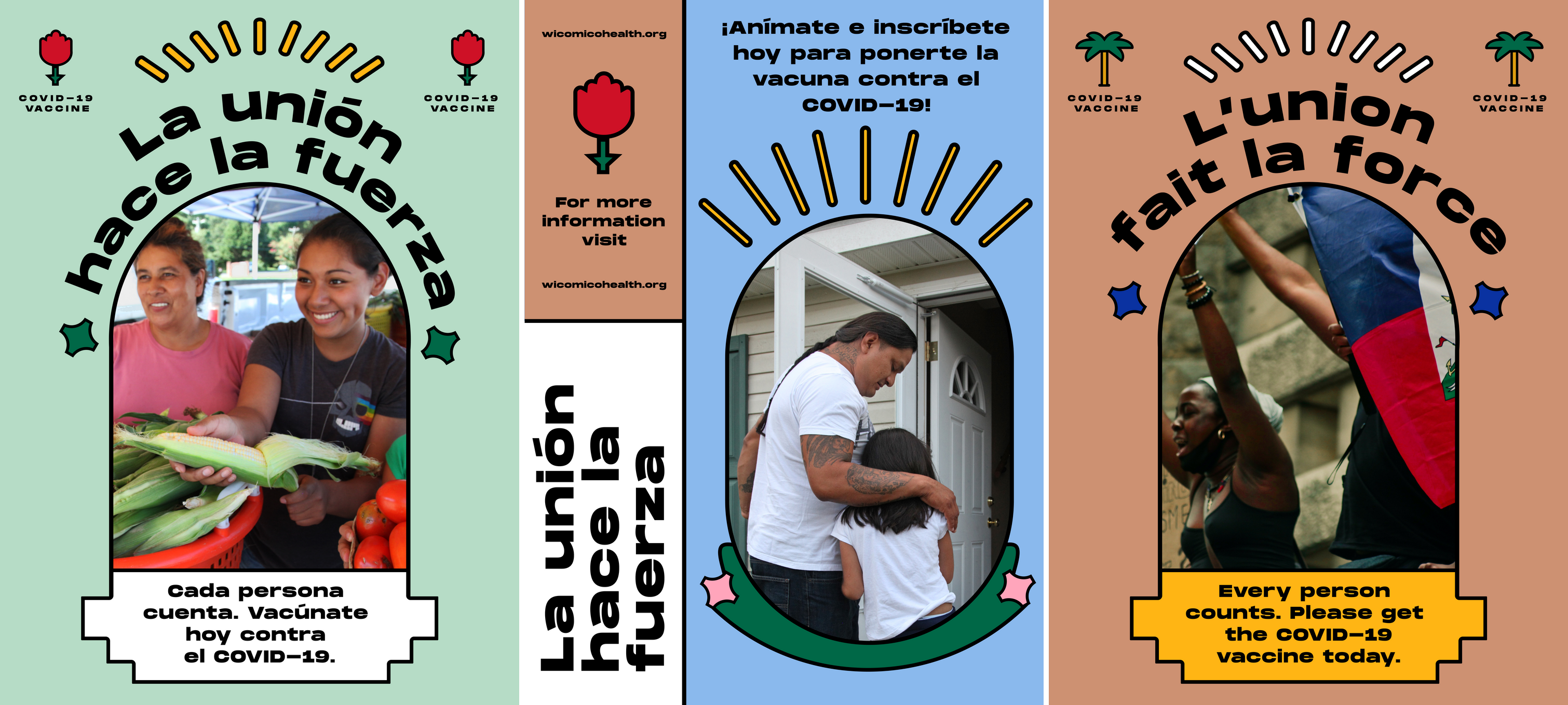

At IDEO.org we usually partner with people in the social sector around certain challenges that are aligned with our mission of building a more just and inclusive world. Whether it’s with the partner, community, or local leaders we strive to design with the people that are experiencing these challenges. It’s not enough that we meet with them and ask them to share some of their needs and challenges, because that won’t get us far enough. When we’re designing with people from the community they are in the driver seat, making design decisions based on their experience and expertise. It’s definitely a work in progress, but with each project we are getting better at providing and sharing our tools, creating the space to collaborate, and bringing in our technical design skills when needed. Passing on the power of design to the community is important. If the community isn’t brought into the process from the get go then who will actually bring this vision for change to life? I believe that a design organization like IDEO.org can help facilitate change, but we’re not the drivers of it. So bringing in the community and local leaders from day one is important as it is their vision and challenges that they’re changing, and we’re just their partner along the way.

In terms of how my work has developed over time, I can say that during my sponge phase I took my learnings and applied them at face value. Today, I question what I learned and actively try to unlearn the pieces I don’t agree with in order to be a more authentic and active participant in what I produce. I’m teaching myself more traditional crafts and artistry and looking into understanding the purpose of these skills and how they’ve historically evolved over time. I’m also working on creating accessible tools that empower others to make and produce in hopes of sharing my own power as a creator. I get so much joy from seeing others take an asset and feel empowered to break it and reimagine it as another. That is success in my book.

What are you looking forward to seeing in the submission entries in this competition? What would a submission need to have to catch your eye or make you vote on something?

Work that’s veering away from trends, experimenting with new forms and formats, and incorporating unconventional expressions and crafts.

Work that has accessibility and ability taken into consideration.

Work that integrates play and perhaps humor into the process. I want to feel that someone enjoyed the process of making and didn’t just submit it because they believe it’s in line with what “good” looks like.